Nigerian Cinema has come a long way in the last decade. It has seen blossoming global exposure thanks to streaming, improved aesthetics and a growing sense that it could nail the three pillars of the business of film. The only thing missing is the prestige associated with some of the iconic forbearers of African cinema.

There is the sense that Nollywood’s growth is still too tethered to the exploitation video boom of the ‘90s and ‘00s. Log on to Netflix and all the Naija offerings emit a vibe of frivolous chaff. Frankly, it is a bit of a disappointment. Are my expectations too high? Maybe.

The height of my expectations may be down to Nigerian filmmaker Kunle Afolayan and his impressive period piece ‘October 1’. His 2015 film remains one of my favourite cinema experiences, offering the kind of historical and socio-political awareness I normally travel back in time to Francophone Africa for. It is essentially Naija’s most accessible entry into colonial confrontational cinema whilst probing at trauma and violence that laced the birth of a nation.

The heft underpinning ‘October 1’ places it firmly in the neo-Nollywood class. Azeez Akinwumi Sesan in his paper ‘The Rhetoric of Return in Kunle Afolayan’s Film October 1’ notes that it slots into “a tradition of quality that advances the technical and dramatic components of Nigerian films.”

This manifests in the inspired casting, noteworthy cinematography and layered script despite the chronic limitations. In the end, audiences are rewarded with a textured story about how Nigeria’s independence, much like a chunk of sub-Saharan Africa, was built on foundations of trauma, exploitation and violence. That the white supremacist colonialists were lording over a fraught ethnic dynamic could only go one way, is one of the arguments Afolayan posits.

Writing about ‘October 1’ and Nigeria as an outsider, I welcome critiques to my assessment that offer more insight. As I have gleaned from this film since I first saw it in 2015, I imagine there are some layers that may be lost in proverbial translation. Like the finest African Cinema, however, ‘October 1’ proves to be instructive for the rest of the continent amid the struggle for decolonisation.

That there is enough nuance in this film to latch on to and appreciate is in line with more rigorous assessments of neo-Nollywood that highlight the importance of a more open-ended approach to storytelling and respect for the audience.

Like the film’s thoughts on the birth of Nigeria as we know it, it opens with violence. A predator hounds a fleeing woman in a scene with an alarming reddish aesthetic. He catches up to her, rapes and strangles her to death. The last act of this man, who we will come to learn is a serial killer, is to carve into her with a razor. The sense of mystery and unease that follows this opening is almost the same for the prospects of an independent Nigeria.

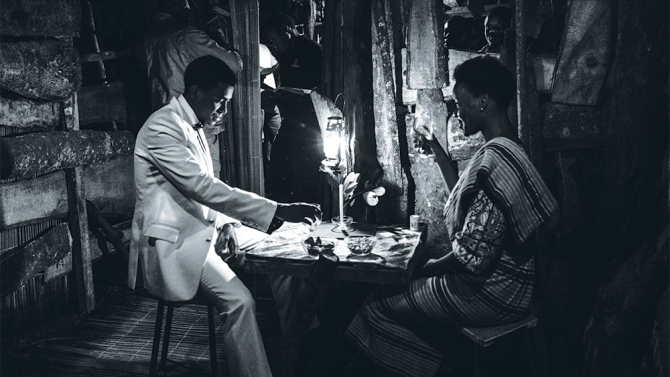

Enter the worn and lanky Inspector Danladi Waziri (Sadiq Daba), or Danny Boy, as he is referred to in a jovial but condescending manner by his British superiors. We are in the film’s present timeline, a little after Nigerian independence. Waziri has solved the serial killings in the town called Akote and is presenting his report to Winterbottom (Nick Rhys), a colonial official. The British had wanted a clean slate and the case of serial murders closed before relinquishing political control.

The tensions here, mostly psychological, are evident. The Union Jack still flies proudly and a portrait of the queen leers oppressively into Waziri’s soul as he prepares to narrate the investigation to us. The British flag and the portrait would be taken down by the time a film came to a close, a small moment of triumph. But a domineering aura always lingers in my recollection of the film.

One of the most important causalities of colonial rule was truth. It meant the colonialists shied away from confronting the generational havoc wreaked on Nigeria and the rest of Africa. This is demonstrated in the handling of Waziri’s findings, which implicate a man educated by the crown and the clergy.

Spoilers from here on. Check out the film on Netflix if you can.

The serial killer is the first person that catches our eye as the film flashes back to the early days of the murders in Akote. In the village square, we witness the fanfare on the return of the village’s prince, Aderopo (Demola Adedoyin), who oozes charm like it’s his second nature. He has returned from the city the first university graduate Akote has produced. Much like the joy he engenders, he was to cause much more grief. That he is almost always clad in white is the first red flag.

The weight of the narrative is to be judged by the why; why the charming Aderopo would resort to killing Akote’s virgins. This assault on innocence is a manifestation of the hurt and betrayal buried in the manner Aderopo lost his own innocence.

As Waziri probes, all trails lead to offcuts of imperialism. A British priest had offered higher education with one hand to Aderopo and chipped away at his soul with the other by molesting him. In one swoop, Afolayan attacks one of the altars in the miseducation of the average African as far as the legacy of colonialism is concerned. Christian religion and western education were not brought in a vacuum and are not “advantages” of colonialism.

Aderopo isn’t the only victim dragged down this traumatic path. We meet a farmer named Agbekoya (played by Afolayan), who is briefly a suspect in the murders. One of the victims is found on his farm. Waziri’s detective work later reveals Agbeyoka was also a victim of sexual abuse by the British priest. But he gave up on his educational dreams to halt the abuse. Aderopo was not strong enough.

Agbeyoka’s trauma is more internalised. Whilst Aderopo lashed out at the world, carving crosses into all his victims, the farmer’s repression sees him and his family turn his back on anything western; the English language, formal education and, of course, Christianity (which isn’t western per se but you get the point).

This thread in ‘October 1’ is in conversation with the complex discourse around Afro-Pessimism given the ripple effects of colonial oppression, both macro and micro, on the small village of Akote. The larger effect of what feels like a conspiracy is evident in the history books and the trajectory an independent Nigeria took. Afolayan spotlights the rotten foundation of Nigeria with not only the insidious corroding effects of Christian actors but in the way in which the truth of the killings was handled.

Winterbottom and a fellow colonial officer lay the final brick in the foundation of deceit by burying Waziri’s findings. This was an indicator of what had happened in the past to Nigeria; like how the operations of the Royal Niger Company (which led to Nigeria as we know it being bought for £865,000), and indicators of what lay ahead for Nigeria given the way Britain’s political and economic interests in Nigeria manifested in unconscionable policies during the Biafran war.

Of course, thoughts on the Biafra war point one towards the delicate ethnic balance. Thousands of Igbos were murdered in a pogrom sparking a chain of events culminating in the Eastern Region of Nigeria formally seceding seven years after the nation’s independence.

In ‘October 1’, not only is the truth of the serial killings in Akote buried, it is buried in the name of ethnic harmony in the trading town. Early in the film, we are treated to scenes of the three main ethnic groups in Nigeria; the Hausa, Igbos and Yoruba living in relative harmony. There is a nice bar with chill vibes in which they all gather to drink at night and you can feel the longing of Afolayan for what could be.

But our director is acutely aware of what is. He harnesses ethnic tensions with key plot points as Waziri’s investigation unravels. Consider the point where the grieving father of an Igbo girl kills a Hausa man in police custody who is but a suspect caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Those acquainted with ‘The Gods are Not to Blame’ will know that Aderopo is a Yoruba name.

The parallels to postcolonial Nigeria’s socio-political and historical experience are clear. The awareness but lack of regard for the ethnic balance and callous rush to depart without putting to bed the ethnic and political crises have cost West Africa’s largest nation over the years.

Aderopo, having been snatched into the abyss by the claws of colonialism, is deeply cynical of the prospects of Nigeria’s liberation. “My educated opinion tells me that independence has arrived ten years early,” he says.

Afolayan sides with the character; not just because his cynicism was justified by time but because of the empathy he has for Aderopo’s scarred soul. Cladding the character in white most of the time is probably the film’s way of compensating for the darkness within and reminding us of what should have been before the drops of crimson splattered across his attire. I believe the use of white also signals the crimes of the white man in Nigeria. Aderopo, after all, walks around whistling the tune to God Save the Queen.

For as much as they tried to cover up, the white man did not leave with a clean record. Even the resolution of the case, which the British desired, uncovered more rot which the British proceeded to bury.

Waziri is aware of British hypocrisy. He just never confronted it. He is well regarded and chosen to look into the Akote murders because he closed a case involving the murder of a British man in Enugu. We later learn the British victim had a Nigerian man flogged to death for theft and was later killed by the man’s father. This father was hanged for his act of vengeance after Waziri closed the case.

The guilt in Waziri’s tone is palpable as he recounts the harsh complexities of this case in a drunken stupor to fellow officers whilst in Akote. At this point, he already feels the heavy shadow of injustice on the horizon.

He gets to make up for this by overlooking Agbeyoka’s confession to a murder of his own; the suffocating of the priest who molested him. This time, Waziri is comfier in the grey areas of this constructed reality.

He is afforded the chance for further redemption in this case and eventually stands up to his British superiors for what feels like the first time. It is a powerful moment when he breaks free of the gaze of the queen and demands that Winterbottom, a man young enough to be his son, call him by his full name, not “Danny Boy.”

There is a melancholy underpinning the narrative and rightfully so. You get the sense that as independence beckoned, the likes of Waziri would be too old to draw on the exhilaration of liberation. Oppression was sadly all they knew.

But even more tragic are the likes of Aderopo and Agbeyoka; meant to inherit the glorious future but too scarred by oppression to ride the wave of independence.